(Bonus) Building Bridges of Hope Vol. 2: Strengthening Co-Parenting and Family Bonds

Guest chapter in the anthology on alienation, co-parenting, and strengthening the family.

I am happy to announce that I was included as a guest author in Building Bridges of Hope Volume 2, published by Hope4Families and Kids Need Both on November 28th, 2025.

I am one of many authors in this anthology, alongside experts like Dawn Endria McCarty, Dr. Alyse Price-Tobler, Danica Joan Dockery, John Stenner Hamel Jr., and many more.

I retain rights over my chapter, so I have copied it below for you to read for free. With that said, I encourage you to get a copy of the book, as it offers many other powerful insights from my co-authors. I do not make anything from book sales, save for the small Amazon affiliate commission if you purchase it by clicking the button below.

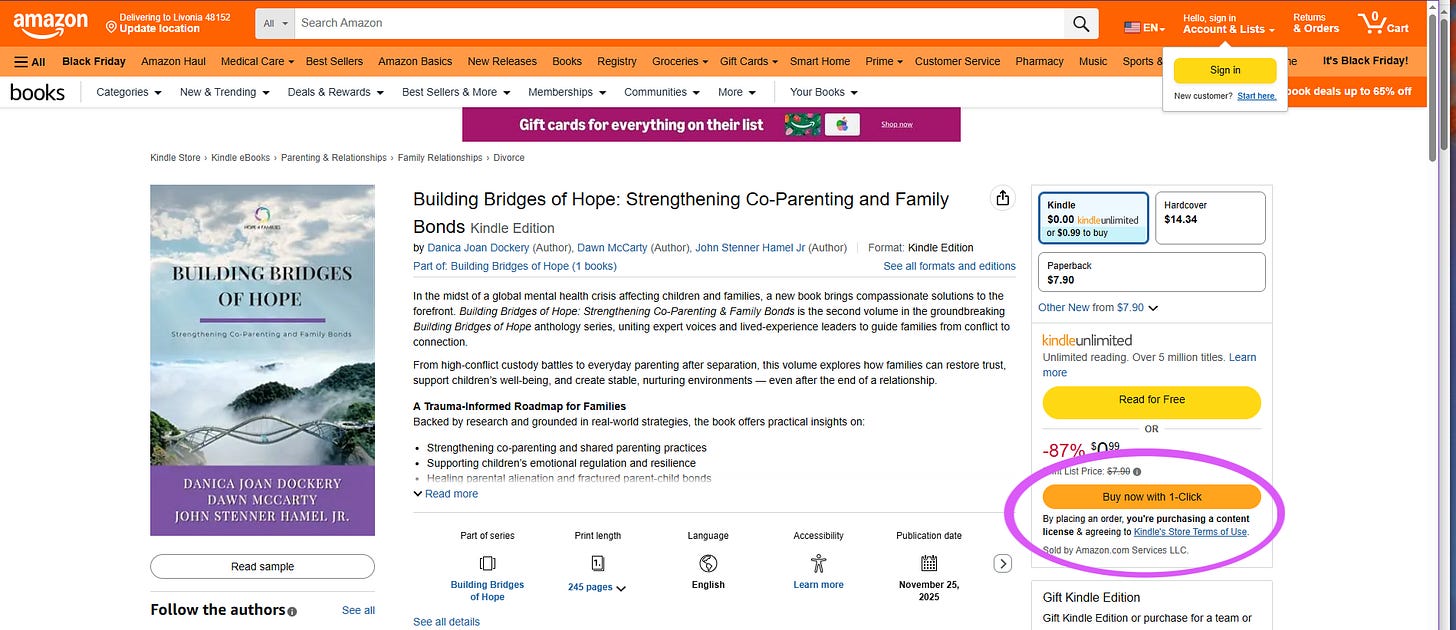

If money is tight, there is a short-term promotion where you can get the book for free on Kindle. All you need to do is go to the Amazon page and select “Buy now with one click.”

Make sure the price listed is $0.00 to ensure you are getting the Kindle free. Remember, this promotion will only be available until Saturday, December 6th, 2025.

Once you claim the free Kindle version (or if you buy it after the promotion), you can access it here. Physical copies are also available at a reduced price for a limited time only.

Another way you can support the book at no cost is to suggest it to your local library for inclusion in their system. Some libraries don’t take donations, but you can ask them to purchase the book so that it is available for the public to read. Every library system might be different, so ask the front desk first what their policies are regarding adding books to their system.

If you are a long-time reader of Shortening the Red Thread, you may see some recurring themes in this chapter that I have covered in previous articles. While some of it may be a review, the essence remains critical to reuniting with your alienated child. But you will also see some newer ideas shared below, particularly the story about Franz Kafka and the little girl who lost her doll.

I was also interviewed by the book team on November 29th. You can view the entire interview below, and for your convenience, the time stamp for my portion starts at 1:24:58.

As always, I hope this is helpful in your journey to reunification. Enjoy the chapter, and stay tuned for the upcoming December edition of STRT, which will be published on December 1st at 10 am ET.

Roots and Wings

“There are two things’ children should get from their parents: roots and wings.”

~ Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

There is a famous story about the writer Franz Kafka and a little girl who had lost her doll. Kafka was strolling through a park in Berlin one day when he came across a young girl crying because she had lost her doll. Kafka helps her look, and unfortunately, they couldn’t find the doll.

And so, he tells her, “Let’s come back again tomorrow, and we will look again for your doll.”

The next day came, and again, after a long search, they found nothing. However, this time, Kafka hands the girl a letter signed by the doll. The letter says, “Please don’t cry, I went away on a trip. I promise to write to you every week about my adventures.”

And so, every week, Kafka would write a new letter as the doll and read it to her in the park. One day, Kafka buys a new doll and hands it to her. The little girl is puzzled, and she says, “This doesn’t look like my doll at all...”

Kafka reads to her the final letter, where it says, “My travels have changed me, and I don’t look like the doll you remember, but deep inside I am still the same.”

I find the story of parents reuniting with their children after alienation to be similar. Trauma can permanently alter our perspective, and for children, it can shape their outlook on life, influence their worldview as adults, and impact their ability to thrive. No parent wants their child to suffer, and the wounds of being kept apart due to circumstances beyond their control lead to feelings of self-doubt and lost identity.

Not all hope is lost. As a child grows up and leaves an abusive environment—be it from alienation or other forms of child psychological abuse—the parent has a unique opportunity to guide their child toward a life better than what they had left behind. The challenge, though, is threefold:

The child the parent sees before them and the one they remember are two different people.

The seemingly irrational behavior of the formerly alienated child throws the parent off kilter, leaving the parent feeling anxious, apprehensive, and sometimes afraid of their own child.

A parent's capacity to lead their child depends entirely on their ability to lead themselves.

In the case of alienation and child psychological abuse, an adult child will typically leave the abuser after a specific breaking point. This breaking point can be, but is not limited to:

Repeated fights about personal autonomy and freedom.

Setting boundaries around verbal and psychological abusive behaviors

Witnessing verbal and psychological abuse toward loved ones like a child, romantic partner, or other family members. Can be one-time or continuous.

A collapse of the narrative they were raised with.

Realizing that “love” was conditional on compliance with the demands of the alienator.

The emergence of their own identity and the abusive parent’s hostility toward it.

A pivotal experience outside the home that shows them what healthy looks like.

While any one or combination of these events will lead to the child leaving their abuser, there is no guarantee that they will have the capacity to process their need for healthy boundaries, expectations in a relationship, and self-image. They are likely to be hungry for truth, looking to unravel the narratives that shaped their perception for so long. This brings intense fear as they lose faith in their ability to see reality as it is. They will be doubtful, testing their alienated parent in fear of finding a hidden flaw that would justify the prolonged separation. Little digs and testing behaviors don’t go away until the child learns the parent is safe. When a parent is reuniting with their child after alienation, they have to anticipate these behaviors, while acknowledging that the child they lost is not the child that returned to them.

The realization can be harrowing for a parent, especially when all the promised memories that come with raising a child are taken. We spend 95% of our time with our children between the ages of 0 and 18. After that, they go out and take on the world. Here, the parent has to reconcile that the relationship they could have had with their child has passed, and the present demands a new approach altogether. Reuniting with an alienated child is not merely resuming an interrupted relationship, but rather the beginning of a new one.

How to Rebuild Your Relationship After Alienation

One misconception about alienation is that parents think they only need to reunite with their child to undo the trauma. Alienation does not end after reunification; it ends with healing. When a child is returning to their alienated parent, they have only experienced unhealthy and toxic relationships. They have little to no bearing in setting up healthy boundaries or meaningful connections with others, especially those who are different from them. This places a great deal of responsibility on the alienated parent, as they will be instrumental in their child’s relational education. The following guidelines are based on anecdotes shared by formerly alienated children and adults, as well as my own experiences.

1. Create a Balance of Family Rituals and Extraordinary Experiences

One of the defining feelings of an alienated child is a sense of apprehension. There is a lurking feeling that something might explode at any moment, and the worst part is that they never know when it will happen. You can become skilled at recognizing the signs of an impending volcanic eruption, but knowing it’s coming does little to mitigate the impending devastation.

The instability and chaos leave the child in a perpetual state of survival mode. When they return to the alienated parent, these skills are brought home with them. They are anticipating you to behave like their abusive parent without even realizing it. To begin repairing and healing your child’s psyche, you must first examine the family rituals and experiences you will introduce into your new relationship.

Family rituals are recurring, mundane events that create a new sense of normal for your child. This can include, but is not limited to:

Cooking meals for the family.

Watching shows or movies together.

Playing games together.

Attending community events like church together.

Sending each other photos, videos, or memes regularly.

Regular phone or video calls.

Listening to music together.

Recommending books or other entertainment to each other.

Performing acts of service (car maintenance, running errands, etc.)

While it may seem small or insignificant at first, these routines give your child something they have rarely had… predictability. Each repeated interaction tells their nervous system that you are steady, reliable, and emotionally safe. Over time, these rituals become the scaffolding that supports deeper conversations, shared vulnerability, and every moment of honesty that follows.

At first, your child is likely to feel like a fish out of water. Between the dread of anticipating conflict and the unworthiness ingrained in their identity, the child may even engage in provocative behavior with the intent of testing whether you are who you say you are. Their questions may feel loaded. Their tone may feel sharp. They may withdraw abruptly, escalate minor issues, or interpret neutral moments as rejection. None of this is personal, and most of it is unconscious behavior. It is an attempt to confirm or disprove the internal narrative they were raised with.

With enough consistency, the mundane family rituals will become part of their comfort zone. They will participate more and will think about them when they are feeling down. If you take a moment to think about your favorite moments with your loved ones, you might think about small moments of sharing good food, conversations with friends or family, or evenings spent together without anything remarkable happening.

These moments stay with us because they are emotionally safe and secure. They allow us to relax, to breathe, and to feel connected without effort. For an alienated child, these moments become corrective experiences. They slowly overwrite the internal expectation that relationships are unpredictable, volatile, or conditional. As these routines become established, you may notice your child initiating them on their own. They might send the first text, suggest watching a movie, or ask to grab dinner. These small shifts signal that the relationship feels less like walking on broken glass and more like a place they can return to without fear of harm. The rituals give them something to hold on to.

In addition to family rituals, you will also need to make room for extraordinary experiences. These moments break the rhythm just enough to show your child that life with you is not limited to routine. Extraordinary experiences do not need to be expensive or dramatic. They simply need to be different from the daily pattern.

Examples of extraordinary experiences include, but are not limited to:

Going on a vacation together.

Attending an uncommon event like a concert or sporting event.

Trying a new restaurant together.

Visiting a museum, exhibit, or cultural festival.

Spending a day exploring a nearby city or town.

Taking a class or workshop together, such as cooking, pottery, or art.

Going on a hike, nature walk, or outdoor adventure.

Participating in a volunteer activity or community project.

Attending a family celebration or meaningful tradition.

Sharing a special milestone experience, like a graduation or ceremony.

These experiences create contrast. They expand the emotional range of the relationship and help your child associate you with moments of curiosity and enjoyment rather than vigilance or fear. They also offer opportunities for spontaneous connection—laughing together, navigating something unfamiliar, or sharing an environment where the rules of their past do not apply.

What makes these experiences effective is the groundwork laid by your rituals. Without the stability of routine, extraordinary moments can feel overwhelming or performative. But when they are paired with a consistent foundation, they become anchors that your child will remember long after the moment has passed.

2. Communicate With Curiosity

Alienated children often return with a deep fear of being misunderstood, and they will likely assume you will react the way the alienating parent reacted. Even if you have never behaved that way, the child’s nervous system has been trained to prepare for the worst. Curiosity is how you disrupt this pattern. When you communicate with curiosity, you replace assumptions with understanding. You give your child room to express their fears, frustrations, and confusion without feeling judged or corrected. Curiosity is not complicated. It means asking questions that help you see the world through their eyes.

Examples of curious questions include, but are not limited to:

“Can you tell me more about what you meant?”

“What feels most important to you about this?”

“How are you interpreting what happened?”

“What were you hoping for when you said that?”

“What would help you feel more comfortable right now?”

Keep in mind that genuine curiosity is a new experience for your alienated child. They may worry that you are digging for information that can be used against them. The alienator commonly does this, so their fears are warranted. Over time, especially when paired with consistent family rituals, you can alleviate that fear and show them that you are not trying to win an argument, attack them, or force a particular narrative. You are trying to understand them as they are now.

Alienated children often struggle to articulate their emotions. Their communication may feel indirect, sharp, vague, or defensive. Instead of challenging their tone or content, you can reflect their emotions back to them so they feel seen. This helps them regulate without feeling pressured.

Examples of emotional reflections include, but are not limited to:

“It sounds like you’re feeling overwhelmed.”

“It seems like that situation caught you off guard.”

“It sounds like you’re worried about being misunderstood.”

“It seems like you’re frustrated that this keeps happening.”

These reflections signal that you are not only paying attention but also trying to understand their experience. By asking questions and deepening your understanding of their experience, you avoid one of the greatest pitfalls alienated parents face… being stonewalled after misinterpreting their emotional state. Curiosity also protects the relationship from unnecessary escalation. When your child senses that you are seeking to understand rather than defend, they begin to feel more relaxed. They feel less need to posture, test, or brace themselves. Over time, this approach teaches them that difficult conversations do not lead to punishment or humiliation, but to clarity.

The goal is not to interrogate or analyze them. Your goal is to create an emotional environment where honesty feels possible. Curiosity gives your child the freedom to reveal who they have become, and it allows you to build a relationship with the adult in front of you—not the child you lost, and not the child you hoped they would be.

3. Co-Create the Relationship

When an alienated child returns (especially after many years), both of you are stepping into a space that no longer resembles the relationship you once had. The longer the separation, the more difficult it becomes to slip back into family roles. The parental authority that would have felt natural years ago now feels awkward, artificial, or even intrusive, and the child has grown up with one or more surrogates to fill in your absence. That is just the reality of alienation. Your child has spent years navigating life without you as an authority figure. They learned to make decisions, handle conflict, and form their worldview without your guidance. Trying to step back into a traditional parenting role often creates tension because it clashes with the identity they built in your absence. This is why co-creation matters.

Co-creating the relationship means letting go of the fantasy that you can return to the past. Instead, you build something new together based on who both of you are now. You are not parenting a young child. You are creating a bond with an adult who carries wounds, questions, and a lifetime of narratives about who you are. At this stage of life, your role shifts from that of an authoritative parental figure to a wise mentor who appears when the student is ready. You offer guidance without forcing it and provide stability without demanding authority. You remain a source of wisdom, encouragement, and clarity, but you do so with the humility of someone joining a story in the middle.

Examples of co-creation may include:

Deciding how often to communicate and at what pace feels comfortable for both of you.

Discussing what kind of support they want from you now, not what you used to give.

Being honest about what feels hard for each of you without placing blame.

Choosing meaningful rituals and experiences that fit your present, not your past.

Agreeing on how to navigate misunderstandings or emotional flare-ups.

Co-creation does not diminish your identity as a parent. Yes, it will be different than the relationships of a typical parent and child, but it will be your relationship. You are building something new with foundations strong enough to hold the weight of the years you lost and the trauma both of you endured. When both of you contribute to shaping this new relationship, you create a connection that is honest, flexible, and capable of growing with you for the rest of your lives.

4. Take Ownership of Your Emotions

Many parents ask, “What about me? What about my emotions? What about all the things I suffered and endured during the alienation and with the alienator?”

And they are right to ask these questions. The burden and traumas of alienation also affect them. The fear, helplessness, and grief of being cut out of your child’s life—none of that disappears simply because the child has returned. Those wounds live in the mind and body, and they deserve real acknowledgment. But this is where parents must understand the distinction between what belongs to them and what belongs to their child.

Your emotions from the alienation are yours to carry, process, and heal. The years of confusion, the invalidation from the system, the pressure to stay composed in the face of injustice—these experiences demand their own space. They require support, understanding, and often professional help. They may also require you to share your story with people who can hold its weight.

Your child cannot hold that weight for you.

Not because they don’t care, and not because your emotions are too much, but because they are still untangling their own feelings. They are still trying to understand what was real, what was distorted, and who they are now that they have left the alienating environment. If you place your emotional burden on them, even unintentionally, they may feel responsible for your pain. That responsibility overwhelms them and reinforces the very dynamic they are trying to escape. When you show your child that you have taken ownership and accountability over your emotions, you are modeling what emotional maturity looks like in real time.

This does not mean suppressing your emotions or pretending you are unaffected by the past. It means knowing where to bring them and how to hold them. Sometimes that means speaking with a therapist. Other times, it means leaning on a friend, a spouse, or a support group. Sometimes it means taking a moment alone to steady your breathing before responding. You do this work so that when your child looks at you, they see a steady presence rather than a fragile one. They see someone capable of guiding them without losing control or defaulting to shame.

Roots and Wings

When an alienated child breaks free, multiple emotions take hold—loss of identity, aimlessness, apprehension, and overwhelm. In short, they have played the role of the alienated child for so long that they don’t know who they are. For a child to succeed in the world, they need to have the stability of roots and the courage of wings. Alienation gives them neither. Their roots were severed through manipulation, fear, and distorted narratives. Their wings were clipped by conditional love, emotional volatility, and the constant threat of punishment for having an independent identity. When they return to you, consciously or not, they are searching for both.

There is a famous poem by Kahlil Gibran that encapsulates our role as parents. While we hope our children will grow in the direction we envision, life rarely unfolds as we expect. Alienation forces every member of a family into roles they never chose, and the return from that story requires courage from the parent first. We must be willing to face the challenge before us, not only for our own healing, but also for our children and their future children, who will inherit the family patterns we either confront or pass down.

On Children by Kahlil Gibran

And a woman who held a babe against her bosom said, Speak to us of Children.

And he said:

Your children are not your children.

They are the sons and daughters of Life’s longing for itself.

They come through you but not from you,

And though they are with you yet they belong not to you.

You may give them your love but not your thoughts,

For they have their own thoughts.

You may house their bodies but not their souls,

For their souls dwell in the house of tomorrow, which you cannot visit, not even in your dreams.

You may strive to be like them, but seek not to make them like you.

For life goes not backward nor tarries with yesterday.

You are the bows from which your children as living arrows are sent forth.

The archer sees the mark upon the path of the infinite, and He bends you with His might that His arrows may go swift and far.

Let your bending in the archer’s hand be for gladness;

For even as He loves the arrow that flies, so He loves also the bow that is stable.

Liked the Bonus Chapter? Here are Some Other Articles I Have Written that Go Into Greater Depth On the Same Topics.

Are you a writer on Substack?

If you write articles on alienation or estrangement, let me know! I would be happy to exchange recommendations to better support our readers.

If you are a general reader who writes about other topics on Substack, please consider recommending Shortening the Red Thread, as that helps other parents find this newsletter so they can get the support they need to reunite.

As always, I deeply appreciate your support and am grateful for your feedback as I develop these articles.