Seeing through the Eyes of the Alienated Child

Learn how to recognize what your child needs without them telling you - STRT May 2025

“Emotions are just messages from the body. When we learn to listen to what those messages are saying, it helps us become better teachers, parents, and leaders.”

~ Mr. Chazz Lewis, Early Child Educator

It is Not About the Nail

A few years ago, I saw a short video skit called “It’s not about the nail.”

In about 90 seconds, the video showcases one of the most common communication challenges in a relationship. In this skit, a couple is trying to talk about a problem that the woman is having. Her partner listens to her talk about her pain and headaches until suddenly, the camera shows the source of her pain—a giant nail jutting out of her head.

The man, trying to be a logical problem solver, goes straight to the solution and says that the pain would leave if she took the nail out of her head. The woman responds angrily, telling her partner that he is not listening to her and that it is not about the nail in her head.

You can view the skit below.

Most people miss the message of the video.

They assume that the video is a play on stereotypical gender dynamics, as though it were simply about how men are logical and women want to talk about their feelings. I first saw this video in my early twenties and shared the same perception. And that perception was utterly wrong.

The point of the video is not about gender dynamics or feelings vs logic.

The video highlights the couple's communication gap. Both people talk about two entirely different things without listening to each other. It is too easy to see how active listening would help the woman with a nail in her head. However, the true value of the video lies in the things that were not said.

Had the man taken the time to listen and validate her emotions and pain, he would have had a better chance of helping her realize the truth than directly attacking the problem.

And underneath the story is a truism about human communication and neuroscience that has been true for as long as we have been able to communicate. The human brain is deeply complex, but you don’t need to be a neuroscientist to understand the basics.

When you are with your alienated child, you will likely be in a similar situation as the couple in this video—the difference is that you are just replacing the metaphor of the “nail” with alienation.

Your child won’t listen to logical explanations about Munchausen by proxy, parentification, enmeshment, emotional incest, or other forms of psychological abuse. And it is not a function of their intelligence. Your child won’t see the truth because they are in a state of pain where they cannot use their executive functions (logic, problem solving, deep observation, etc). Additionally, if your child is still under the age of 25, their brains are still actively developing.

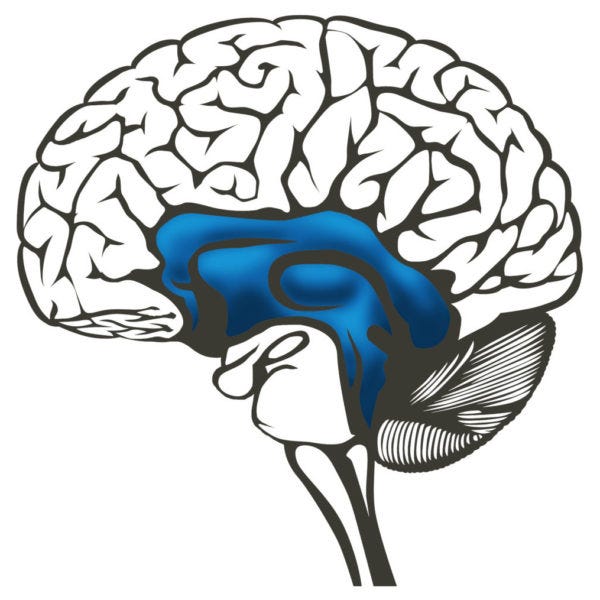

The brain has three basic states: survival, emotional, and executive. The more stress the brain is under, the more likely it is to be in an emotional or survival state. De-escalating conflict with your alienated child is as simple as learning to identify what state the child’s brain is in at that moment and guiding them back to an executive state.

The following model I will share below is the Brain State Model from Conscious Discipline. You can learn more about them through their website or purchase their book, “Conscious Discipline: Building Resilient Classrooms.”

Note: This book is written for teachers and early childhood educators, but I still found value in it as a parent. You don't need to get the book if you don’t want to; I will explain the big idea below.

And the best part…you don’t need to be a neuroscientist to understand it.

Survival State

Also known as the “lizard brain,” the brain stem controls one of the most important brain states—the survival state.

The survival state kicks you into action when you fear for your well-being. It is that feeling when the hairs rise on the back of your neck, your mind goes into high alert, and you can move very quickly should the need arise.

At the core of survival is the avoidance of death. We want to ensure that we live long and fruitful lives while avoiding the great unknown. Here is a list of things that trigger our innate fear of death:

Physical harm

Ostracism or separation from other people

Decline in health

Fear of the unknown

Loss of control or autonomy

It should come as no surprise that alienation can encompass all five of these factors, affecting both the alienated child and the parent. When one or more of these fears are triggered, your mind drops all executive function and focuses solely on self-preservation.

Think back to a time when you were caught in the maelstrom of alienation—an argument escalating into violence, loved ones who once trusted you suddenly call you a horrible person, or staring at an overdrafted bank account while knowing you have a month’s worth of bills on their way.

In those moments, your mind is solely focused on what is happening in the moment. You won’t care about whether you mowed the lawn yet or if the fridge has enough groceries. It is hard to care about starving children in Africa when it feels like your world is burning down. And that is not your fault.

In survival mode, cortisol (the stress hormone) is released, putting you on high alert. In extreme situations, your body produces adrenaline, propelling you into action.

So, how does this relate to alienation?

An alienated child is often subject to a myriad of psychological, emotional, and physical abuse techniques meant to kill their sense of personal autonomy and train them to become an enabler of the alienator.

When an alienated child’s nervous system is locked in the survival state, the amygdala is firing like a car alarm while the pre‑frontal cortex (their “executive office”) has gone dark. In that state, they make a brutally pragmatic calculation: Where is it safest to discharge or suppress this panic so I don’t get hurt, and what do I do to ensure my safety?

Because the alienating parent controls the child’s access to love, shelter, and social belonging, open defiance (fight) or escape (flight) toward that parent would invite immediate retaliation in the form of a loss of privileges, ridicule/harassment, threats, or further emotional manipulation.

To stay physically and emotionally safe, the child’s brain defaults to freeze (“If I stay small and invisible, maybe I won’t be attacked”) or fawn (“If I mirror the alienator’s beliefs and please them, maybe I’ll stay safe and earn a scrap of approval”).

Conversely, the targeted parent feels safer; there is less risk of catastrophic punishment. That safety paradoxically gives the stress energy somewhere to go. Hence, the child’s limbic system redirects the repressed fight-or-flight impulse toward the targeted parent, manifesting as angry outbursts, verbal attacks, running to another room, slamming doors, abruptly ending visits, ghosting phone calls, or exhibiting avoidant behavior.

In the child’s trauma‑skewed logic, “It’s safer to explode or be avoidant here, because this parent’s love won’t be withdrawn and the consequences won’t feel life‑threatening.”

Thus, the same survival circuitry that once protected the child from genuine danger is hijacked by the dynamics of alienation, producing seemingly irrational but perfectly adaptive behavior given the child’s perceived landscape of risks and rewards.

To address the survival state, you must recognize that the child is seeking to answer the question, “Am I safe?”

Let’s explore the four survival reactions in greater detail and how you can provide them a sense of personal safety.

Fight

When an alienated child lashes out, the survival brain is screaming, “I feel unsafe, so I must scare the threat away.” The fury you see is a flare sent up by hidden fear. Like a charging elephant, the child tries to overwhelm the perceived danger with sheer volume and force.

You cannot fight fire with fire in this case.

Anger needs fuel. If you meet it with more anger, you are pouring gasoline on the fire and handing the reins of the moment to the child’s panic‑driven brain. Chaos follows, and the situation escalates. In extreme scenarios, violence may occur, and sometimes the police are involved.

Instead, fight fire with water. Maintain a still posture, slow your breathing, use a level tone, and keep your eyes steady. Your nervous system broadcasts safety, and the child will recognize that you are in control. There is a powerful video below of a man standing calmly as an elephant charges at him. Notice how he does not yell or curse, nor does he run. The elephant notices that the man is not scared of him and realizes that picking a fight is not a good idea, even though the elephant is much larger than the man.

Remaining calm, especially in the face of adversity, also demonstrates real power. Power is not something you demand; it is a state you embody. By standing grounded while the storm rages, you keep authority vested in you, the adult, where it belongs. Responding with anger signals that the child is in control of the situation, undermining your role and escalating the chaos you hoped to prevent.

“An attack is proof that one is out of control.”

~ Morihei Ueshiba, The Art of Peace

The best way to win a fight is not to join it.

When your child makes angry demands or tries to provoke you, stay calm and composed. Remember: anger feeds on reaction. By not engaging in the emotional tug-of-war, you maintain control and teach them that respect, not volatility, is the path to connection.

You might say:

“[Child’s name], I don’t respond to disrespectful language. If you’d like to talk with me calmly, I’m here and willing to listen. However, I will not continue this conversation until we are both speaking respectfully. I also hope you won’t let anyone speak to you that way either. You deserve kindness, and so do I.”

Notice how the language you use is only about what you will do.

I don’t respond to disrespectful language.

I will not continue this conversation until we are both speaking respectfully.

This communicates your boundaries and that you have the self-respect to uphold them. You are not making demands because the child will undermine you by going against them anyway. Instead, you stand your ground with poise and calm. And you communicate what YOU will do.

Flight

In the survival state, flight is the brain’s attempt to escape a perceived threat. For an alienated child, this often shows up as avoidance—ignoring texts or calls, refusing visits, staying silent, or giving short, cold answers. While it may appear like indifference or even cruelty, this behavior is actually rooted in fear.

The alienating parent often interrogates the child after any interaction with the targeted parent. “What did you talk about? What did they say about me? Did they try to manipulate you?” The child quickly learns that the less they do, the less they have to report and the less punishment, guilt, or psychological warfare they must endure. Avoidance becomes a survival strategy: If I don’t engage, I stay out of trouble.

But it’s not just external pressure from the alienator. Internally, the child may be grappling with guilt or shame. Ignoring the targeted parent’s messages can feel easier than facing the pain of what they’ve done or said under the alienator’s influence. To acknowledge the relationship would mean confronting their own hurtful actions—something their nervous system is not yet ready to do. So they run. Not because they don’t care, but because it feels safer not to feel at all.

Flight, like all trauma responses, is not a rejection of love. It is a desperate attempt to survive a world where love has been weaponized.

One of the most common mistakes alienated parents make is trying to do too much, too fast, especially when the child is in flight mode. The instinct is understandable. You might want to clear the air, discuss the alienation, explain what really happened, and resolve the misunderstanding. However, when your child doesn’t feel safe with you yet, such a conversation feels like stepping into a trap.

It’s like the YouTube video “It’s Not About the Nail,” where the partner is trying to solve the problem when all the other person wants is to feel understood. When a child is avoiding you, it’s not the time to pull out explanations, timelines, or emotional appeals. Right now, they aren’t wondering what’s true.

They’re wondering if it’s safe.

So instead of launching into heavy conversations, tune in to everyone’s favorite mental radio station: WII FM—What’s In It For Me?

If your child’s nervous system is still in survival mode, the best way to connect is through low-stakes, enjoyable topics that interest them. Pop culture, hobbies, music, video games, favorite YouTubers, anime, sports, the latest superhero movie—these are safe ground.

These are conversations they can have without fearing backlash from the alienator later. Because let’s be honest… if the alienator is going to grill them after every visit or call, it’s much easier for them to say, “We just talked about Taylor Swift,” than “We talked about how I miss you.”

These seemingly superficial conversations are not a waste of time. They’re an invitation back into connection, and connection is the bridge to healing. Safety comes first. Trust follows.

Only after that can deeper conversations even begin.

Freeze

The freeze response is often misunderstood because it looks like nothing is happening. There’s no yelling, no running, no emotional outbursts—just stillness. A blank stare. Monotone answers. Shoulders curled inward. Delayed responses. A child who seems far away, even when they’re right in front of you.

But make no mistake… a freeze response is a full-body alarm. An alienated child who has entered emotional shutdown is not being cold or distant. They are in a protective state of dissociation.

This is their nervous system saying, “If I can’t fight, and I can’t flee, I’ll disappear on the inside instead.”

Dissociative behaviors (numbness, zoning out, disconnecting from emotions) are powerful survival tools. When the pain feels unbearable and no safe adult is available to help, the mind decides: If I don’t feel it, it can’t hurt me.

The child isn’t rejecting you; they are trying to survive a reality where love and belonging are conditional, and the cost of feeling might be too high.

Freeze is especially common with the alienating parent, who often punishes emotional expression or independence. However, it can also surface with the targeted parent, particularly if the child anticipates being asked to feel or say something they don’t yet have the safety to express, such as affection, remorse, or vulnerability.

How to Support a Child in Freeze

When your child is emotionally shut down, the key is not to pull, but to wait and witness with care. Here’s how you can help:

Create safety through quiet presence. Don’t push for eye contact or conversation. Sit near them without expectation. Your calm energy is the message: You are safe here.

Avoid “Why” questions. These trigger the thinking brain, which isn’t accessible in freeze. Use gentle observations instead:

“You seem really quiet right now. That’s okay. I’m here with you.”

Offer grounding, not fixing. Touch a soft object together, hum a simple tune, or sit in nature. Grounding brings the body back from numbness to awareness, without forcing emotions to rise too quickly.

Respect their pace. Silence is not rejection, it’s recovery. Each moment you stay regulated while they’re shut down builds trust in your presence.

Give small, empowering choices.

“Would you like to sit here or over there?”

“Do you want to draw, or just rest?”

The freeze state softens only through continuous relational safety. When your child senses that they won’t be punished, pressured, or emotionally overwhelmed in your presence, their nervous system can begin to thaw. That’s when healing begins, not through long conversations, but through your unwavering, gentle commitment to meet them exactly where they are.

“Although we rarely die, humans suffer when we are unable to discharge the energy that is locked in by the freezing response. The traumatized veteran, the rape survivor, the abused child, the impala, and the bird all have been confronted by overwhelming situations. If they are unable to orient and choose between fight or flight, they will freeze or collapse. Those who are able to discharge that energy will be restored. Rather than moving through the freezing response, as animals do routinely, humans often begin a downward spiral characterized by an increasingly debilitating constellation of symptoms.”

~ Peter A. Levine, Waking the Tiger: Healing Trauma

Fawn

The fawn response is the nervous system’s way of creating safety through submission and appeasement. In the context of parental alienation, fawning becomes a survival strategy—a child’s way of staying on the good side of the alienating parent, who often holds love and approval as a form of leverage.

Fawning can look like excessive flattery, mimicking the alienator’s beliefs or attitudes, overly helpful behavior, or quick emotional attunement to the alienator’s moods. Over time, this develops into deeply ingrained people-pleasing behaviors—a pattern of constantly managing others’ emotions to feel safe and accepted.

For the alienated child, love has become conditional. They learn that if they say the right thing, act the right way, or make others happy, they’re less likely to be punished or rejected.

While fawning is most often directed at the alienator, it can appear in subtler and more complicated ways with the targeted parent, especially if the child has been away from the alienator for a period of time. You may see:

Blame shifting – “It wasn’t my fault, it was [someone else]!”

Love bombing – Sudden intense affection followed by a request or emotional withdrawal.

Emotional deflection – Pushing your buttons so you direct your anger somewhere else.

Another fawning behavior that often goes unrecognized is tattling or “snitching”—not to be helpful, but to redirect danger away from themselves. The child might report a sibling’s behavior, or even exaggerate something another adult did, to ensure that you are angry at someone else instead of them.

It’s a form of emotional diversion rooted in fear: If I control where the punishment goes, I won’t be the target.

At the same time, the child may also fear that if they don’t tell you, you’ll be mad at them for hiding something. So they snitch to avoid blame from both sides. It’s a no-win situation that reflects their deep need to stay safe in emotionally volatile environments.

How You Can Support a Child in Fawn

The alienated child doesn’t always know when they’re fawning. To them, pleasing others feels like love, because that’s how they’ve been conditioned to receive care and avoid conflict.

As the targeted parent, your job is to gently separate love from performance. You can help them unlearn these patterns by:

Naming the behavior without shame: “You don’t need to protect yourself with compliments or stories. I care about you no matter what.”

Creating emotional safety: “You don’t have to make me happy for me to love you.”

Not overreacting to tattling or blame shifting: “Thank you for telling me. I’ll handle it. And just so you know, you’re safe even when you make mistakes too.”

Modeling genuine, unconditional love: Love them on their quiet days. Love them when they’re sulking. Love them when they offer nothing at all.

Fawning is not manipulation in the adult sense. It’s a trauma-adapted behavior meant to survive power imbalances. And it dissolves, not through confrontation, but through safety, modeling, and time. When your child learns that they don’t have to please you to keep your love, they begin to heal and reclaim their sense of self.

Emotional State

When a child begins to feel physically safe with you, their nervous system slowly steps out of survival mode and into what is known in Conscious Discipline as the emotional state. This shift is subtle but significant. The child is no longer solely focused on protection—now they are seeking connection.

The question that guides their behavior shifts from “Am I safe?” to something far more vulnerable: “Am I loved?”

For an alienated child, this question is loaded with complexity. They are often torn between conflicting loyalties, internalized guilt, and a deep-seated craving to feel accepted again by the parent they have been taught to reject. In this state, their behaviors are no longer about fighting or fleeing danger. They are about finding a place to belong.

What Belonging Looks Like

It’s easy to overlook the ways a child expresses this desire for love and connection, especially when the signs are subtle or wrapped in inconvenient behaviors. Parents might dismiss emotional bids by saying things like, “He’s just trying to get attention,” without realizing that attention is the currency of connection.

Here are some common signs that a child is operating in an emotional state:

Playfulness – They make silly jokes or tease gently, trying to open a low-stakes doorway to connection.

Curiosity – They ask about your childhood, favorite movies, or “Did you ever play Pokémon Go?”

Validation-seeking – They might ask, “Do you like this drawing?” or “Did I do it right?” as a way of checking if they’re still worthy of your approval.

Personal sharing – They bring you something they care about—a meme, a favorite toy, a random fact—and wait to see your response.

Mild testing – They may push a small boundary or make a sarcastic comment, gauging whether your love holds firm.

Requests for help – Even in things they can do themselves, like tying their shoes or choosing clothes, what they’re really asking is, “Are you willing to show up for me?”

Emotional vulnerability – They might become tearful, mention missing something small, or share a self-critical comment, inviting you to see their softer side.

Each of these behaviors is a bid for connection. The question isn’t “Do I get what I want?”—it’s “Do I matter enough to be seen and responded to kindly?”

In these moments, alienated parents often want to affirm their child, but how you affirm them matters. The way you speak into your child’s emotional state can either build trust or unintentionally reinforce the belief that love must be earned.

Judgments are value-laden statements that tie a child’s worth to how they behave. For example:

“You’re such a good boy.”

“I’m glad you behaved today.”

“You’re the smartest kid I know.”

These may sound positive, but they teach the child that love and approval depend on performance. If they fail to meet expectations, they may internalize the belief: I’m not lovable unless I’m pleasing someone.

By contrast, encouragement recognizes effort, growth, and intrinsic qualities. It affirms without grading. For example:

“You worked really hard on that.”

“I saw how patient you were with your brother.”

“You made a really thoughtful choice.”

Encouragement helps the child feel seen for who they are, not just praised for what they do. It fosters internal motivation and resilience, rather than people-pleasing and emotional overfunctioning.

To shift your language:

Start with phrases like “I noticed…”, “You showed…”, or “I appreciate…”

Focus on actions and traits instead of assigning identity labels.

The Brain Chemistry of Connection

Connection isn’t just a feeling—it’s a biological event. When a child feels loved and accepted, their brain releases chemicals like dopamine and oxytocin. These hormones:

Regulate emotions and reduce stress

Strengthen bonding and trust

Support impulse control and long-term behavioral regulation

In other words, every time you respond to your child’s emotional bid with encouragement and warmth, you’re not just building a better relationship—you’re literally rewiring their brain toward healing.

The emotional state is fragile and transitional. Your child might show affection one moment and withdraw the next. That doesn’t mean you did something wrong. It means they are still learning what love feels like when it’s not conditional.

Here’s what alienated parents should remember:

Notice the subtle cues—jokes, questions, small acts of sharing.

Respond with encouragement that uplifts their character, not their performance.

Stay emotionally steady even when feelings swing.

Avoid performance-based love—don’t overpraise or overgive to win their approval.

Show love even when nothing is earned.

Each time you meet their emotional needs with presence, patience, and unconditional love, you answer their quiet question—Am I loved?—with something they desperately need to believe:

“Yes. Always. No matter what.”

Executive State

After safety has been established (“Am I safe?”) and connection has been nurtured (“Am I loved?”), the door finally opens to the most powerful state of the brain: the executive state. This is where true healing begins.

The executive state is governed by the prefrontal cortex—the part of the brain responsible for reflection, emotional regulation, decision-making, empathy, and long-term planning. It’s the state we need to be in to learn, grow, and live with purpose.

The guiding question of the executive state is:

“What can I learn from this?”

This shift in thinking marks a profound turning point for alienated children. When they enter the executive state, they are no longer reacting to the world through fear or emotional dysregulation—they are responding to it with insight, curiosity, and intention.

But here is the catch.

You cannot force a child into the executive state, but you can create the conditions that allow them to reach it. This happens by consistently answering the earlier questions with your actions:

“Am I safe?” → answered through your calm, grounded presence

“Am I loved?” → answered through encouragement, unconditional care, and consistency

When a child’s body and heart begin to trust these answers, their mind becomes free to engage, reflect, and rebuild.

This is when the deeper work begins.

In the executive state, your child will begin to develop the emotional maturity needed to make sense of what they’ve been through. They may start to:

Ask more reflective questions

Express remorse or gratitude

Acknowledge past behaviors with honesty

Set healthy boundaries (with you, the alienator, or others)

Initiate deeper conversations

Take responsibility for their own actions without collapsing in shame

This is the space where your child can begin to reclaim their authentic self—the version of them that isn't reacting to someone else's control or shaped by a distorted narrative, but instead is rooted in self-awareness and integrity.

The shift to the executive state doesn’t just help repair the parent-child bond—it sets your child up for success in every area of life.

Children who spend more time in the executive state are more likely to:

Set and achieve personal and academic goals

Develop meaningful friendships and healthy romantic relationships

Handle conflict without escalation

Advocate for themselves and others

Experience fewer symptoms of anxiety, depression, and hypervigilance

Approach life with confidence rather than fear

In short, when your child no longer has to burn their energy on survival, they can invest it in their growth.

And that’s the real gift you offer them. Not just reconnection, but the foundation for a healthy, thriving future.

As a targeted parent, your role is not to lecture, fix, or force your child to heal. Your role is to create a relational environment where safety, love, and truth are felt so consistently that your child naturally begins to operate from their highest self.

When they are ready, they will ask, “What can I learn from this?”—not because you told them to, but because they finally feel free enough to wonder.

That moment, when it comes, is nothing short of sacred.

Tying it all together

When I reunited with my mother after almost 13 years of alienation, I wasn’t operating from logic or reflection. I was still finding my way out of survival mode. On the surface, I appeared calm. Inside, I was guarded, conflicted, and unsure how to bridge the years of pain and the terrible things I had once said and believed about her. I knew my past behavior was unfair, and frankly, reprehensible. But I didn’t know how to face it, let alone repair it.

What made all the difference was how my mother responded.

She never guilted me. She never demanded apologies or explanations. And she never told me what to do. She gave me respect and autonomy that felt so foreign to me after years of being tightly controlled by my alienating stepmother. My mom gave me space to be myself, which felt both strange and healing.

She always does everything she can to stay connected. She would pay for our flights so I could come visit her. She’d take us out to eat, not as a bribe or obligation, but simply as a way to share time and joy. She always told me how proud she was of me, never for what I did, but for who I was. Her words and actions, over time, answered a question I hadn’t even realized I was asking: Do I still belong here?

She always made sure I did.

And when my daughter was born, she showed up in every way she could. She held her, played with her, asked thoughtful questions, and became a steady presence—not just in my child’s life, but in mine. In many ways, my daughter became a bridge that brought us even closer, healing wounds that no conversation ever could.

The Brain State Model Isn’t Just for Kids

While this model is typically used to understand children’s behavior in a classroom setting, the model still works outside the classroom, and it’s just as powerful—and necessary—for adults. Many targeted parents are navigating their own trauma, grief, and emotional dysregulation. And many formerly alienated children are now grown, still carrying the scars of conditional love and unresolved shame.

If you’re an adult trying to reconnect with your child—or with yourself—this model offers a framework for reflection:

Survival State (Am I Safe?)

Do you feel overwhelmed, reactive, or emotionally numb?

Are you operating from fear, control, or exhaustion?

Are you avoiding vulnerability or lashing out to stay protected?

If yes, pause. First, find ways to regulate your body, such as practicing breathwork, engaging in grounding exercises, or taking a moment of stillness.

Emotional State (Am I Loved?)

Are you seeking validation from others to feel okay?

Do you find yourself people-pleasing or second-guessing your worth?

Are you over-apologizing, withdrawing, or reacting strongly to rejection?

These are signs that your need for connection and belonging isn’t being fully met. In this state, practice self-encouragement the way you would offer it to a child. Surround yourself with relationships that affirm who you are, without conditions.

Executive State (What Can I Learn From This?)

Once your nervous system is grounded and your emotional needs are acknowledged, you can transition into the executive state. This is where clarity, growth, and change happen.

Ask yourself:

What’s this moment teaching me?

What do I want to build from here?

What boundaries, routines, or changes will support me staying regulated?

Alienated children who are still under the control or heavy influence of the alienating parent are most likely operating in the survival state, where behaviors are driven by fear, control, and self-protection.

On the other hand, children who have begun to break free from the alienator’s grip are more often found in the emotional state, where they are cautiously seeking connection and trying to understand where they belong.

It’s important to remember that these brain states are not fixed labels—they are fluid and can shift based on context, environment, and relational cues. This framework is not intended to diagnose, but rather to help parents orient themselves and more accurately interpret their child’s behavior based on where they might be in their healing process. Use it as a starting point, not a rulebook, and always respond to the child in front of you, not just the behavior you see.

This process isn’t linear. You or your child may move between states in a single day. But the more time you can spend in the executive state, the more resilient, connected, and aligned you’ll feel. You will be able to find meaning despite the alienation.

More importantly, you can be the foundation your child stands on, allowing them to find their meaning through the trauma.

Whether your child is a toddler or an adult, they may not yet have the emotional tools to self-regulate, especially after years of alienation. Their brains are still developing (or still recovering), and their perception of safety, love, and identity has been shaped by distortion.

But you can become the steady anchor they return to.

When you model groundedness—when you stay calm in the storm, offer love without strings, and affirm who they are instead of what they do—you provide the relational safety they need to develop trust again.

And over time, they will mirror you.

They will learn to ask “What can I learn from this?” not because you forced them to, but because your presence gave them the safety to grow.

Overall, the Brain State Model offers more than a parenting strategy—it offers a relational blueprint. One that can help you reconnect with your child, rebuild trust, and even heal the fractured parts of yourself.

Whether you’re trying to reach a child still caught in alienation or repairing the wounds as an adult child or parent, this model gives you a starting point:

Build safety with calm, consistent presence.

Build connection through unconditional love and encouragement.

And when readiness arrives, walk with them into reflection, growth, and healing.

Love won’t fix everything overnight. But love, practiced with intention, can rebuild everything that matters. And that, more than anything, is what opens the door to coming home.

Liked this Article? Here are a Few Past Articles You May Like…

Escaping the Prison of the Mind (A great follow-up on the emotional state after alienation).

How to Talk With Your Alienated Child When They Don't Want to Talk To You (Good for navigating the survival state with your alienated child).

Finding Meaning in Alienation When All Hope is Lost (Helping you grow in an executive state).

Additionally, be sure to watch the followup discussion I have with the Anti-Alienation Project based on this article.

Book Update

Some of you might have heard that I am working on a book about helping parents reunite with their kids.

I am still in the early stages of development, so I have a lot of research and planning to do before much writing can be done. With that said, I am making small steps of progress each month. I don’t have a concrete timeline yet, as I'm balancing parenthood, a full-time job, and freelancing.

That said, I like to think this newsletter helps me stay accountable :)

Feel free to ask any questions; I may even turn your question into a newsletter.

If you liked this article, please share it with someone who you think would benefit from it.

Until next time,

Andrew Folkler

Are you a writer on Substack?

If you write articles on alienation or estrangement, let me know! I would be happy to exchange recommendations to better support our readers.

If you are a general reader who writes about other topics on Substack, please consider recommending Shortening the Red Thread, as that helps other parents find this newsletter so they can get the support they need to reunite.

As always, I deeply appreciate your support and am grateful for your feedback as I develop these articles.

Your advice in this article is invaluable to me. I have been in a frozen state of limbo, terrified to move in any direction for fear of causing more damage to my daughter. I feel mortified and ashamed it took me so long to figure out what was happening. You have armed me with the exact knowledge I have been relentlessy seeking and the confidence to move forward knowing not only what she needs most from me, but how to properly go about it without damaging her further. I cant thank you enough. Your book will be amazing. I will definately be buying. There isnt anyone I know who wont benefit from what you have to say. Amazingly insightful. Great writing!

Thank you Andrew. This is so helpful. The more we understand the more we can try to help our children.